As an avid reader I am saddened by where novel publishing has gone in recent years. Like so much in America today it is formulaic, simplistic, bland and boring. The old authors are just pumping out trash for cash and the interesting new guys never get a chance.

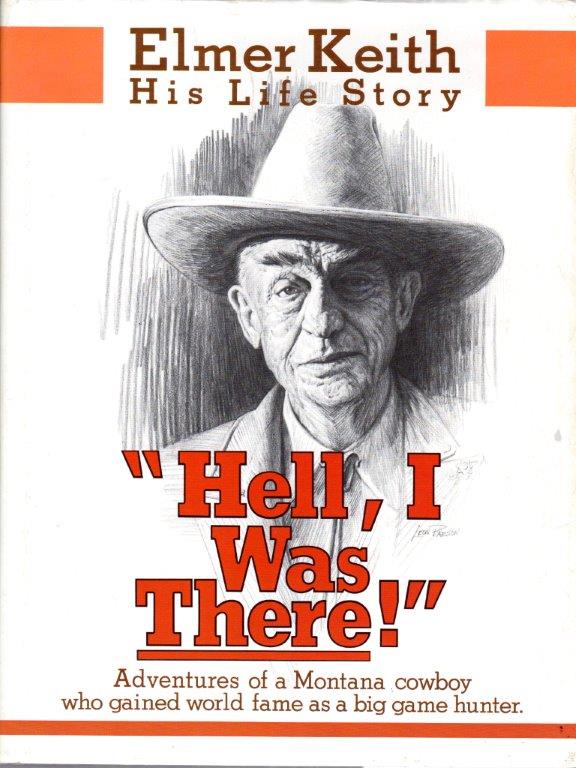

I was bored to tears from all this homogenized “literature” and was browsing the forgotten bookshelves in my abandoned “old” office for something to read. I stumbled onto Elmer Keith’s autobiographical book “Hell I Was There” and sat down early last night to read. The next time I looked up, it was two AM. I forgot how interesting his work could be.

The rivalry between gun writers Elmer Keith and Jack O’Connor is the stuff of legends. While nobody questions that O’Connor was the more polished and educated writer, it remains a puzzle why few today recognize that Keith was light years ahead when it came to the gun stuff.

Keith was a competitive shooter, an armorer, handloader and an experimenter who developed cartridges and bullets. O’Connor latched onto the .270 Winchester because he didn’t like recoil and somehow got the greater glory.

While Keith is famous for developing the. 44 Magnum, his influence was seen in many magnum pistol cartridges used today, including the .357 and .41 magnums. He was a gun guy with tremendous knowledge about rifles and shotguns as well. He was an experienced hunter and guide who had a lot of experience with big, tough critters like elk and grizzly bears and he recognized the value of a big rifle bullet. Keith developed, or co-developed, cartridges that provided the foundation for the .338 Winchester, .340 Weatherby and .338-378 Weatherby. Perhaps the best known was the .333 OKH (O’Neil-Keith-Hopkins) that used .333-inch bullets from the .333 Jeffery. That .30-06 based cartridge later was changed to take the .338-inch bullets used in the more common at the time .33 Winchester, and it became the .338-06.

Keith is often written off as a small man who favored big guns to compensate. But that is an oversimplification using a lazy reliance on pop psychology to promote something that probably isn’t true. First of all, he was small because when he should have been growing he was recovering from very severe burns that would have killed most people or at the very least crippled them for life. Even after surviving, the doctors said he would never live past 21 years of age. At 21 he was riding bucking horses in rodeos and guiding back country pack trips for elk. He clearly was a guy who didn’t let anything hold him back and didn’t seek out excuses. I don’t think he had a lot of time to obsess about his size. Or maybe that’s what was driving him. Either way, he rose to the top, because of or in spite of his stature. But it didn’t control him.

Keith was a gun guy with an insatiable curiosity. He didn’t just accept the conventional wisdom that is parroted about guns, but wanted to try them all himself and see how they worked. He lived with a gun in his hand every single day and had opportunity to witness more successes and failures than most hunters and shooters would have in a dozen lifetimes.

One interesting aspect of reading this book again is in seeing how much experience Keith had with smaller cartridges, .25-35, .250-300, .280 Dubiel, .30-06, 7X57; the list is very long. He also had a tremendous amount of hunting and guiding experience all throughout the western US, Canada, Alaska and Africa, where he witnessed firsthand how well all these, and many other, cartridges performed on game. That included a lot of sheep hunting and a lot of mule deer hunting, so Jack didn’t have a damn thing on him in that department, either. Keith had much more experience and with a wider diversity of cartridges, bullets and game than O’Connor, particularly in the early part of their adult lives.

Keith started elk hunting with big bore Sharps rifles. He moved on to modern, bottle neck cartridges of various sizes. Finally he came full circle back to the bigger bore guns. Or at least what is now considered big bore. He focused on 33-caliber rifles for big game like elk and bears. Hardly over-compensation but, as most gun guys know, it’s simply smart cartridge selection.

Remember, when Keith promoted the .375 H&H for elk, there were few other smokeless powder cartridge choices. The .300 H&H was around, but extremely rare. In the U.S. we pretty much jumped from the .30-06 right to the .375 H&H and given the crappy bullets of the day, the .375 was a much smarter choice for elk. That said, even with today’s super-bullets I contend it still is.

There is no doubt that poor bullets were a big factor and Keith alludes to that often in this book. Some of the rifle and handgun bullets of the time were horrid. But bad bullets were not and are not restricted to the smaller calibers. Nor are good bullets. Keith decided that even with equal quality bullets the bigger bore rifle and pistol cartridges were better game killers.

The point is that the critics miss the important context of the times and don’t know or don’t care about the facts. Keith was a gun guy, he shot a lot and was very good with any rifle. He wasn’t recoil proof, but he understood that with performance comes recoil and he learned to deal with it. Like most true shooters, he just didn’t figure it was a big deal.

I suspect that O’Connor recognized the value of promotion and in building a legacy, so when Outdoor Life decided to make him a superstar, he latched onto the little known .270 Winchester as his signature rifle cartridge. Keith didn’t care about such foolishness, he was a gun guy who called it as he saw it and never wanted to be restricted by association with one cartridge.

Elmer Keith holds a high position in golden age of gun writers. Even walking among giants he towered above them all.