If you ever want a lesson in confusion try researching the history of the mile. It will make you nuts.

If you ever want a lesson in confusion try researching the history of the mile. It will make you nuts.

There is the Roman mile, the Italian mile, the Arabic Mile, the English mile, the Irish mile, the Scottish mile, the Welsh mile and the Dutch mile. Let’s not forget the German mile, Austrian mile, Prussian mile, Danish mile, Hungarian mile, Portuguese mile, Russian mile and the Croatian mile.

We must also consider the Statute mile, Imperial mile, International mile, U.S. Survey mile and of course the Nautical mile. Don’t forget the Geographical mile, Metric mile, Swedish mile, Norwegian mile and the Scandinavian mile.

It’s enough to make you want to use the metric system!

As far as I can tell it all started with the Romans. They considered a stride the distance the left foot travels for each step when walking. One thousand of those strides became a mile. It all sorted out to today’s accepted 5,280 feet (let’s not even get into how that number was arrived at!)

That’s equal to 1,760 yards, which is a damn long rifle shot. Particularly when the target is one of those cowboy cutouts used in CAS shooting. He is a little dude, smaller than a man and just to be mean, the guys at Barnes Bullets put it five yards past a mile at 1,765 yards.

This was a media event with Barnes Bullets where we toured their factory, ate some great food and burned up a bunch of their rifle ammo at the range. I love shooting OPA! (Other people’s ammo.)

During the drive to the shooting range high in the Utah desert the talk was about the mile long target, so it was of course the first target I wanted to try.

I am having trouble shooting prone this summer due to several factors including a motorcycle accident late last year, so I put the big Remington MRS .338 Lapua rifle on a portable shooting bench. We had to get creative with the bipod for it to work, but after bending the legs like a grasshopper we had the right height.

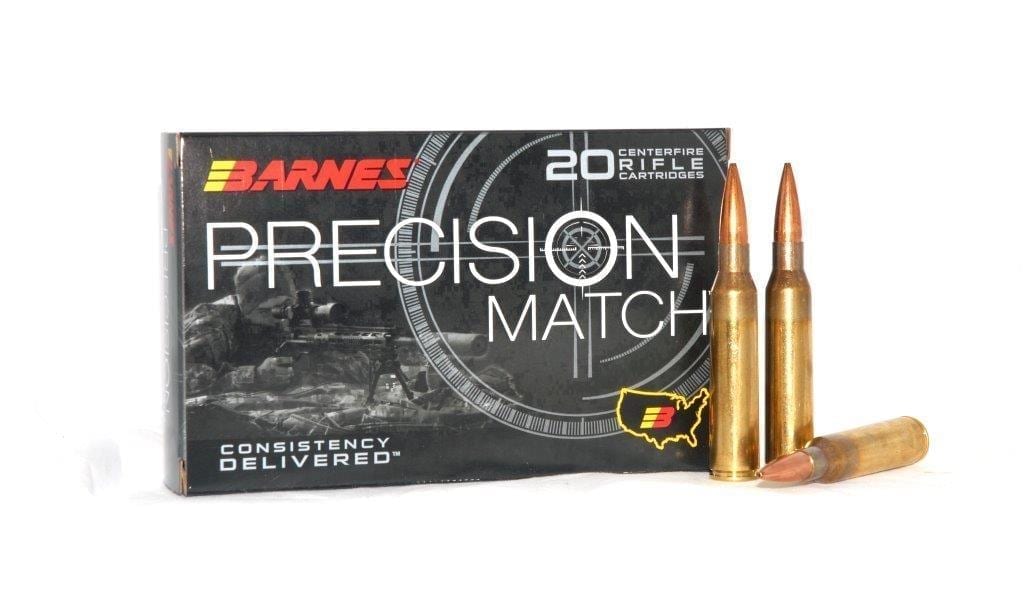

I loaded up with Barnes 300 grain Precision Match ammo. It took a few shots to get the wind right, and with the lighting conditions the spotter could not see hits. We both could see misses kicking up dust. It took so long for the bullet to get there, 3.35 seconds, that even with the recoil of this big cartridge I could get back on target to spot the impact. Once I dialed in, we worked with the assumption that anything not a miss was a hit. I made several before stopping to let the barrel cool.

But I wanted a confirmed, “I can see it clear as day” hit, so I was unsatisfied when I stepped away from the rifle.

Candice Horner took over the gun after it cooled. The lighting had changed enough that the spotter could see the hits and she smacked that steel several times.

I didn’t want to leave it like that so I got back on the gun after it cooled again and hit the target several more times. This time the spotter could see the hits. I gotta say, it’s pretty satisfying to hit a target that small, almost on demand, at more than a mile! It was not the first time I have shot that distance and even farther, but it’s always a treat to hear the spotter call “hit” when the target is in another zip code.

Shooting at ultra-long range is not the mystical and secret feat that some would make it out to be. You need an accurate rifle, good ammo, good optics and a good spotter. Maybe some good luck. At that distance a MOA rifle is, at best, shooting a 17.6 inch group! In our case, the target was not much bigger, so you have to play the odds and not expect every shot to be a hit.

Figuring out the ballistics for the correct hold is math. As with all math, if you put in good data you get a good result. But it’s still only shooting; once you know the hold it’s not difficult if you do it right. What distance does is magnify mistakes, so the key is to not make any.

Other than wind, it’s all physics. Once you understand the hold, it becomes the domain of three things. Your ability to break the shot correctly and the accuracy of the rifle and ammo you are using. The third is the wild card, the wind. With a bullet in the air for more than three seconds there is a lot of time for changing wind or air currents to influence it. Wind is the one uncontrolled factor. Math and science are less important here than art. Reading the wind takes experience and it’s what defines a true master at long range shooting.

In this case we were shooting the ultra-accurate Barnes Match ammo with a 300 grain HPBT bullet. It’s a little known fact that Barnes has developed ammo for the military snipers and they have teamed up with companies like Tracking Point to produce accurate ammo designed for long range shooting. When it comes to long range accuracy, they know their stuff.

Barnes measures the ballistic coefficients for their bullets by shooting in a climate controlled 300 yard underground range. Then they prove it for many of the loads out to ultra-long range using Doppler radar. So when you plug their B.C. into a ballistics program you are putting in good, proven data.

Later in the day I was making consistent 1,200 yard hits with a DPMS AR-15 in 5.56 using the Barnes 85-Grain Match load. This is the first time I have shot past 1,000 yards with a 5.56/.223 and felt like I had control of the outcome. Sure I have hit targets, it was all but random and not very predictable. With this Barnes load I could hit the target almost on demand. I think the reason is that long, heavy, bullet.

Slamming steel at ultra-long range is a lot of fun and it’s turning into a national pastime. I do not condone hunting big game at these distances. There is simply too much that can go wrong. On that long list, and often ignored by those who do advocate hunting at long range, are the terminal ballistics of the cartridge used. At these extreme ranges the bullet energy has often dropped well below accepted standards for big game. Perhaps even more important is that the velocity has often dropped well below the minimum impact velocity to insure bullet expansion. It’s a bad combination.

Tactical applications, on the other hand, are a different thing entirely. The ethics of shooting big game do not apply. If you are shooting for defense against bad guys trying to harm you or your family the rule book doesn’t apply, but the laws of physics still do. That’s why I like the .338 Lapua. Not only does that big, high B.C. bullet stay predictable at long range, it will hit very hard.

Let’s take a look at what we were shooting that day. At 1,200 yards the 5.56 had 173 foot-pounds of retained energy. That’s just a bit more than a .22 LR. The .338 Lapua, however, still carries 1,250 foot pounds of energy. They both start out at about the same velocity, but the 5.56 is down to 958 ft/s while the Lapua’s retained velocity is 1,369 ft/s. Expansion of any bullet is iffy with both cartridges at that velocity, but the odds favor the faster Lapua. Also, consider that even if they don’t expand, the .338 bullet has a 51% bigger diameter and is 253% heavier. Clearly it’s going to do a lot more damage. At a mile, assuming you can hit the target with the 5.56, that cartridge is down to 116 foot-pounds of energy and 785 ft/s velocity. However, the .338 Lapua has 747 foot-pounds of energy left and is still going 1,058 ft/s.

The bottom line here is it’s not just about hitting the target. In a tactical situation, you need to hit it as hard as you can. Other than a .50 BMG, which brings with it a bunch of other baggage, the .338 Lapua is one of the best cartridges for doing that. If you use Barnes 300-grain Match or Barnes VOR-TX ammo with a 280 grain LRX bullet you will extract all this cartridge has to offer.